Shelley’s jilted wife

The tragedy of Harriet Westbrook

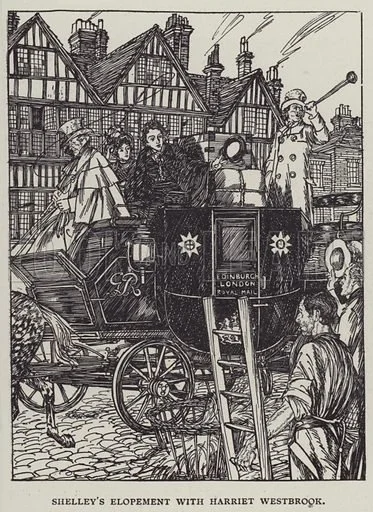

Harriet Westbrook was born in 1795 into a healthy family environment and a promising future. Her father was the owner of a profitable and popular coffeehouse and tavern in Mayfair, London. John Westbrook wanted his children to move up in the world, so he enrolled Harriet at Mrs Fenning’s Boarding School in Clapham. It was here she became a friend of twelve-year-old Hellen Shelley, the younger sister of Percy Bysshe. Shelley met fifteen-year-old Harriet after Oxford University sent him down in January 1811 for expressing publicly in a pamphlet his atheist views. By August 26th, he and Harriet had eloped and were on their way to Scotland to be married. At only 16, his new bride was attractive, vibrant and naïve.

“She had a good figure, light, active and graceful… The tone of her voice was pleasant; her speech the essence of frankness and cordiality… to be once in her company was to know her thoroughly.”

Shelley was dashing, intelligent and impetuous. It’s easy to see why this ‘bad boy’ poet might appeal to such a well-brought up young lady. Shelley was the Regency era’s answer to a rock star. He was sexy, alluring and dangerous. Not surprisingly, after only two years the marriage, was on the rocks and Shelley was laying the blame squarely on Harriet’s shoulders.

Shelley's Elopement with Harriet Westbrook. Illustration for The Life of a Century, 1800 to 1900, by Edwin Hodder (George Newnes, 1901).

The truth was he had grown besotted with Mary Godwin. While just as naïve as Harriet, Mary – the offspring of two of the greatest thinkers of the era, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin - possessed an intellectual brilliance that Harriet – the daughter of a tavern owner – did not. Within weeks of meeting Mary, he had stolen away with his second teenager. Harriet, by this time, was the mother of a one-year-old daughter, Ianthe. She was also pregnant with a second child. Abandoned and betrayed, Harriet returned to her father’s house and suffered immeasurably under the public’s scrutiny.

There is little known about Harriet’s life for the next two years. Her son Charles was born in November 1814 (to whom Shelley endeavoured to be a father), and she remained at the family home in Chapel Street, Belgravia.

Then, suddenly, in September 1816, she disappeared, leaving her children with her parents.

The mystery of Harriet Westbrook

In the early morning of 10th December 1816, an elderly man was making his way through Hyde Park when he saw something floating in the waters of the Serpentine. It was the body of a young woman. He told the authorities that it appeared as though she had been in the lake for some days.

There were no obvious signs of violence, and the natural conclusion reached at the inquest held later was that the poor girl had taken her own life.

A tragic tale, but hardly unheard of in the 19th century.

Drowning in the Serpentine was one of the most common means of suicide in London.. But there are several facts about this story which make it one of the most engaging mysteries of literary history.

The young woman in question had been missing for almost a month.

During that time, she had been living under an assumed name – Harriet Smith.

At the time of her suicide, she was in the final months of pregnancy, even though she had been estranged from her husband for over two years.

The husband in question was the son of a Baronet and Whig MP, the avant-garde poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The Serpentine in London’s Hyde Park

On their return from Europe in late 1816, Shelley, Mary and Claire took rooms in Bath. Mary had already begun writing Frankenstein. It was in Bath that Shelley received a letter from his friend, Thomas Hookham, informing him of Harriet’s death.

Within days, Harriet’s body was buried under a false name, and a brief notice appeared in The Times.

“On Tuesday a respectable female, far advanced in pregnancy, was taken out of the Serpentine River and brought to her residence in Queen Street, Brompton, having been missed for nearly six weeks. She had a valuable ring on her finger. A want of honour in her own conduct is supposed to have led to this fatal catastrophe, her husband being abroad”

The notice omitted her name and it ended with a veiled reference to her fall. The episode was hushed up so efficiently that it begs the question: Did Shelley’s powerful and connected father, Sir Timothy, play a role in the coverup?

It later emerged that she went to lodgings in Hans Place, Knightsbridge, telling the landlady she was married and her husband abroad (a fabrication that skirted the edges of the truth). She used the name Harriet Smith.

The main reason for inventing the story was most likely to account for her obvious pregnancy. Perhaps this was the reason she had fled her parents’ home. While her parents may have been sympathetic when Shelley abandoned Harriet, they may not have been so understanding had she succumbed to his charms yet again. There is a record of the two meeting in London around the time of the child’s conception. After all, they were the parents of Ianthe and Charles, so it is not unfeasible to imagine the pair would come into contact. Likewise, there is no evidence of another love interest in Harriet’s life and, had her parents discovered she had given herself to another man, they would probably have been justifiably annoyed as it was John Westbrook who was housing, feeding and clothing his grandchildren.

On 9 November 1816, Harriet departed her lodgings for the purpose of taking her own life. She left behind a self-reproachful suicide note wishing Shelley all ‘that happiness which you have deprived me of’.

Six days after Harriet’s body was discovered, Shelley wrote a letter to Mary Godwin, absolving himself of all blame. In it, he reveals he believed Harriet ‘descended the steps of prostitution until she lived with a groom of the name of Smith’ who deserted her.

An artist’s rendering of Harriet’s body dragged from the Serpentine

There is no evidence to corroborate these claims.

However, many years after Shelley’s death, Lady Shelley (the poet’s daughter-in-law) seized upon these words. Although she had never met her famous father-in-law (her husband was only three years old when Shelley died), she waged a relentless campaign to restore Shelley’s reputation for the benefit of the Victorian public. A major part of her campaign was to exonerate Shelley’s behaviour towards his first wife. This occurred at Harriet’s expense.

To protect his own daughter’s reputation, William Godwin stirred the pot further by spreading a series of ludicrous rumours. Chiefly, that Harriet had been unfaithful to Shelley even before he had abandoned her. He blackened Harriet’s name by commenting on her ‘low’ social standing, her lack of intelligence and even the possibility that she was an alcoholic. The last comment was probably born from the fact that Harriet’s father was the proprietor of a coffeehouse and tavern.

Biographers and historians have speculated for centuries about how Harriet Shelley died. Some have even suggested that Godwin had her killed. After all, it was Harriet who stood in the way of making Mary an honest woman. They reference Godwin’s diary of the time where he notes Harriet’s death on November 9. However, the date of her death wasn’t known until three weeks later when her body was found. This seems far-fetched as, by this stage, Godwin was impoverished and constantly hiding from the authorities. The writer could never afford to hire a killer and it seems unlikely the intellectual philosopher would carry out the deed himself. The most likely explanation was that he added the entry later. He was an obsessive and meticulous diarist.

Although the public loves a conspiracy, the most likely explanation for Harriet’s death was, as the inquest concluded: she had taken her own life. Shelley had treated her abominably, leaving her to live with all the disgrace he had heaped upon her and, finding herself pregnant again (if by Shelley or not), may have been the final straw in a tragic saga that began five years earlier when she met her best friend’s older brother, the dashing and daring poet, Shelley.